Intro

Hello and welcome back for another serving of Bacon’s Bits, the article series where I get to dig into a niche Underworlds topic and weigh in with my opinion. Continuing the theme of trying to improve your performance at competitive events, today’s topic will be on how to perform self-evaluations after your games. Once again, I do think this is an important area that can often get neglected when we get bogged down in the feeling of losing or overexcited in the aftermath of winning. Particularly in the latter case, it is easy to fall into a trap of “well, I won a game, a set, an event, heck the World Championship, so I must’ve done most everything correctly.” If you listened to our podcast episode on this past year’s World Championships of Warhammer, despite not dropping a set the whole tournament, you heard Aman discussing and even focusing on games where he could have played better. No matter what it is you want to be good at, that desire to do better the next time is the main driving force. To paraphrase American football legend Tom Brady, the sweetest trophy is always “the next one.”

The “Luck” Factor

The nice thing about this exercise is that it is always the same regardless of whether or not you won the game. Yes, odds are that, if you won the game, you would likely have had fewer instances where you failed than where you succeeded. By the same token, if you lost, there were likely fewer instances where you succeeded than where you failed. For the purposes of this analysis, the outcome is actually irrelevant. What is relevant is being able to identify why you failed or succeeded. If you made the correct decision, but experienced a negative outcome, that is no reason to abandon the logic that led you to making that decision.

This is where the first and, being a dice game, perhaps most important area of this discussion lands: luck. You might be surprised to hear that luck is a relevant factor in an article about improving your competitive game play, but identifying which player got “lucky” is extremely important. For example, “ah, I would’ve won, but my opponent got a crit defence right when they needed to!” Often, this can feel bad, but what were the circumstances surrounding that? I cannot count the number of times I’ve seen someone tilt over a crit defence after having charged in to make an attack that had less than a 50% chance of hitting. There is actually a defined term for this called “negativity bias.” The human brain naturally weights negative experiences more heavily than positive ones, which is why you may feel irritated when your opponent crits in these scenarios, then, after the match, point back to such events as instances of where luck was not on your side while forgetting to mention the cases where you were the lucky one.

While I am not so naïve as to think that random elements like dice and card draw order never impact the outcome of a game, it is important to calibrate your response in the context of the actual probabilities of certain outcomes rather than the outcomes themselves. This is not to say that it is never worth making an attack that has less than X% chance to hit, just that every decision you make should be weighted to the probability of its outcomes. If an attack has low odds of success, you should be making it at minimal risk and/or maximal reward. The higher the odds of success, the higher amount of risk I am willing to incur (note that there should still be some reward/goal in mind when you take that risk). The way I generally “track” this in my post-game review is to look at both my favorable and unfavorable outcomes, determine what the probabilities of success were in those outcomes, and then evaluate my decision-making afterwards. I even track “lucky” and “unlucky” notes in my spreadsheets where I document my games (something I typically generate only when I am in the beginning stages of learning a warband). The most key points to check, in my opinion, are pure 50-50s. Things like who won the roll-off in R2 or R3 can have a huge outcome on a game, and knowing whether that was a determining factor either in my favor or not is key. It is similarly important to look not only at particular instances of luck, but at the wholistic body of luck throughout the game. If I roll a single-die crit defence in the last activation, that is “lucky,” but if that is the only defensive crit I rolled all game, then that is actually “unlucky,” as I would say luck during the early-mid game is generally more impactful than luck in the late game.

The “Skill” Factor

Once we’ve determined the luck factor, we get into the more nebulous field of looking at our decision-making. There’s no sugarcoating it, this can be very difficult. The “correct” decision is so dependent on any given game state that it is hard to give blanket advice in this category. This is especially true given that we can only do so in the context of information we may have learned at a later point in time. The “best case” is to make decisions which both promote your own scoring and inhibit your opponent’s. I kill your fighter holding an objective in no one’s territory so that I score XYZ kill surge plus bounty while you don’t score your [![]() Icy Grip]

Icy Grip] or such. Meanwhile, the “worst case” is making a decision which does not actively promote your gameplan while also not actively disrupting your opponent’s. Presuming minimal other factors at play, these should be pretty straightforward right/wrong decisions. However obvious these decisions might be (and yes, you should be evaluating to make sure you got these right, at least), my experience has often been that the most important decisions lie much closer to the median. Let’s say you have a choice: score a 2‑glory end phase card while allowing your opponent to score their own or deny both of you from scoring that end phase. Which do you pick? In a vacuum, it is impossible to know, so it is important to apply context. Who was further through their objective deck? Who was more starved for unspent glory? How likely were those cards to be scored at a later time and would holding onto them until then pose further detriments to those players? These are all things that need to be considered in order to identify whether you made the “right” play.

or such. Meanwhile, the “worst case” is making a decision which does not actively promote your gameplan while also not actively disrupting your opponent’s. Presuming minimal other factors at play, these should be pretty straightforward right/wrong decisions. However obvious these decisions might be (and yes, you should be evaluating to make sure you got these right, at least), my experience has often been that the most important decisions lie much closer to the median. Let’s say you have a choice: score a 2‑glory end phase card while allowing your opponent to score their own or deny both of you from scoring that end phase. Which do you pick? In a vacuum, it is impossible to know, so it is important to apply context. Who was further through their objective deck? Who was more starved for unspent glory? How likely were those cards to be scored at a later time and would holding onto them until then pose further detriments to those players? These are all things that need to be considered in order to identify whether you made the “right” play.

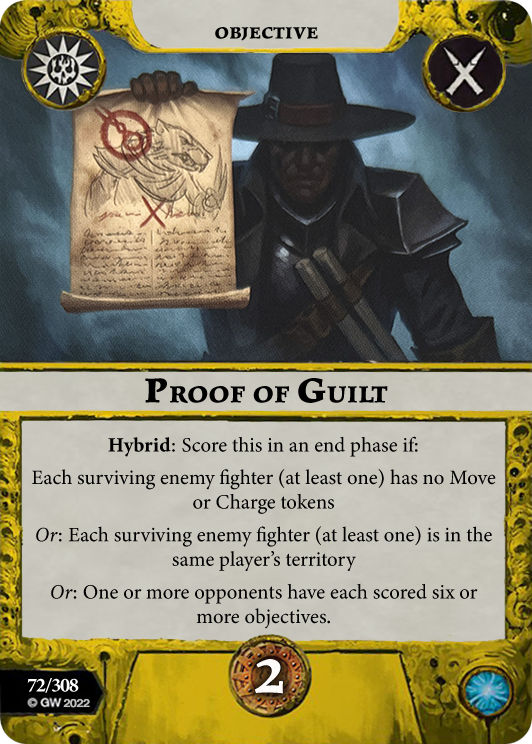

Of course, since we are doing this in the post-game, so we have perfect information as to what our opponent was trying to do/had in their hand at the time of the decision. It is easy enough to sit there and go “well I didn’t know that at the time, so I couldn’t have acted on that information.” This is the kind of thinking that stops you from improving. Believing that a certain event was outside of your ability to predict is the easiest way to let yourself off the hook in a situation where, in reality, you missed something. There is a fine, yet important distinction between what you can predict and what you can control. This is where we start to bleed in a little of last week’s topic. You can’t control dice, but, as we discussed, you can predict what the most likely outcomes are, as well as what will happen if a favorable or unfavorable outcome is obtained. The same is true of cards. You can’t control or know exactly what cards are in your opponent’s hand/deck, but you can predict what they might be. From your games played with or against a warband and/or Rivals deck, you should know what the powerful cards are and the impact they can have on the game. If my opponent scores [![]() Proof of Guilt]

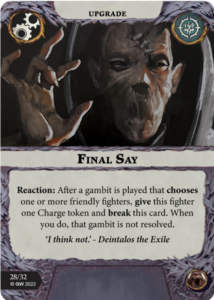

Proof of Guilt] in the first round (presuming it’s not because I have already scored 6 objectives) or voidcurses my Deintalos with [

in the first round (presuming it’s not because I have already scored 6 objectives) or voidcurses my Deintalos with [![]() Reshaping Snare]

Reshaping Snare] , I can’t sit there and say “well, I didn’t know they had it in hand.” Like with dice, you determine the probability that certain card(s) is/are present and then have to accept the risk/reward involved with playing against them. Either you’ve factored in the risk of the card and decided to do something which exposes you to it anyway, or, if that risk is unacceptable, you make an alternative play which can counter that card. It is very important to be able to identify these situations after the game (although it is, of course, ideal to identify them during the game). As I mentioned earlier, you can still have unfavorable outcomes even in cases where you played correctly, but the play was correct only if you actually anticipated what that unfavorable outcome might be prior to taking the inciting action.

, I can’t sit there and say “well, I didn’t know they had it in hand.” Like with dice, you determine the probability that certain card(s) is/are present and then have to accept the risk/reward involved with playing against them. Either you’ve factored in the risk of the card and decided to do something which exposes you to it anyway, or, if that risk is unacceptable, you make an alternative play which can counter that card. It is very important to be able to identify these situations after the game (although it is, of course, ideal to identify them during the game). As I mentioned earlier, you can still have unfavorable outcomes even in cases where you played correctly, but the play was correct only if you actually anticipated what that unfavorable outcome might be prior to taking the inciting action.

Possible Lessons Learned

Since, as I mentioned earlier, it is difficult to give blanket advice without the context in which decisions were made, I figured it best to just list out the things I generally look at to determine whether I played adequately and whether there is room for improvement. Each of these things could probably do with its own article (or even series of articles) given how much variance there might be in what is “desired” as a result of your warband/playstyle choice. However, if you want a checklist…

- Boards – Did the board I selected and its resulting orientation (whether I am the one who placed it or not) help or hinder me in this match? If I placed a board with printed hazard/blocked hexes, who leveraged those hexes more?

- Objective Placement – Who benefitted most from the objective placement? Did I disrupt my opponent’s gameplan/serve my own based on where I placed them and the order in which I placed them? Is there a spot I could have placed XYZ objective that would have been better?

- Fighter Placement – Did I accidentally expose one of my key fighters early? Was one of my key fighters out of position for most of the first round (or even the whole game) as a result of my deployment? Did my fighter deployment allow me to get enough charges off in the first round/deny my opponent enough charges?

- Activation Sequencing – This is a big one I see quite often. Back in the day, the most glaring example would have been charging with all 3 fighters of an elite warband and then using your final activation to draw a power card (the charged-out rule has changed the math on this, in many cases). Even so, the order in which you activate your fighters matters. Even if you aren’t planning to use any cards or abilities to beef up a charge with your most dangerous fighter, holding their activation keeps the threat alive for your opponent and forces them to play around it. It can also mean that you’re not dangling a key fighter for counterpunching as early into the round.

- Denial – Did my opponent score anything that I could have stopped? What steps did I take that led to them scoring—or not scoring, as the case may be—those objectives? What could I have done instead if this situation/matchup comes up again?

- The Beatdown – This goes hand-in-hand with the previous entry, but did I correctly identify who the beatdown was in this matchup (the player more responsible for disrupting the other’s gameplan)? If I did not, what factors did I fail to consider that led me to that erroneous conclusion?

- Positioning – When I charged, how much was I paying attention to where I landed? Did I end up on enough objective tokens to support my own scoring/deny my opponent’s? Were there equivalent hexes I could have charged into that would have improved my short or long-term options? Did I get hit with any “gotcha” cards like [

Reshaping Snare]

Reshaping Snare] or [

or [ Puncturing Ice Shards]

Puncturing Ice Shards] that I could have avoided?

that I could have avoided? - Threat Assessment – Did I identify my opponent’s most dangerous fighter(s)? If I tried to curb the threat by removing them from the battlefield, did I prioritize those kills in the right order/at the right time?

- Opponent’s Plays – If it weren’t enough to keep track of your own play, it is also important to track whether your opponent made mistakes. A weird thing to care about, but, while your opponent’s mistakes may have helped you in the game, knowing what they could have done better is not only a useful thought exercise for yourself, but can also inform you on how much harder the game might have become in an instance where you play against someone who executes better. Conversely, if you felt your opponent played a very strong game, that is also a great learning opportunity, as you can look at the things they did well and incorporate them into your own strategies going forward.

- Deckbuilding – Sometimes, the mistakes come before the game even starts. If you identify cards which were not helpful (whether it was just because of the timing at which you drew them or if you generally just felt they did not assist in what you were trying to do), it is worth noting that was the case. One game is not always immediate grounds for taking them out of the deck—although it can be, if you felt you drew the card at an opportune time and yet still found it lacking—but if a pattern emerges after you play more and more games, you’ll be happy you took some notes to identify this issue and swap it out for a more useful card instead.

Conclusion

While I had to keep the discussion kind of broad given the nature of the topic, I hope this gives some insight into how to dissect your play and key in on areas that need improvement. While it all sounds good and simple when typed up on the page (or screen, I suppose), the biggest factor that I did not discuss in the article is the player (you). You not only need to be capable of performing an accurate analysis of the plays that happened throughout the match, but also do so in an objective manner. We all have times where, whether due to emotional reasons or even just an inherent bias, we look back at our games and still believe we did everything “right.” Don’t worry, that kind of thing happens all the time. I would say that, if you are going through your analysis and not really picking up on any mistakes you might have made, try asking a player (or several) whose judgment you trust, even if it happens to be the person you just played against! So many accomplished players in this game are perfectly happy to answer your questions or provide their input. No matter what your experience level is in this game, don’t be afraid to ask a “stupid” question to a player you believe surpasses you in skill. In fact, I would go so far as to say those are the people you should ask most of your questions to, since they presumably have the largest pool of useful information to share with you. The more you play, talk, and think about the game, the better you’ll get.

Thanks so much for reading and of course, feel free to suggest additional topics if you are enjoying the series! Until next time, we wish you the best of luck (and skill) on YOUR Path to Glory!